Is fraktur an American folk art or an imported European one? One could say “yes” or “no” to either proposition and successfully defend the position. As Don Yoder puts it, fraktur has “roots in the arts of Switzerland and the Rhine Valley but it blossomed and developed in new directions in America. Here it came to form an even more basic part of everyday culture” (Yoder, 1989). The roots were systematically explored by Donald Shelley, beginning with his 1938 research trip to the Rhineland, Alsace and Switzerland where he found “many types of fraktur work. These…reveal almost all the types and techniques which appear later in Pennsylvania but [they are] not as numerous” (Shelley, 1961, p. 24).

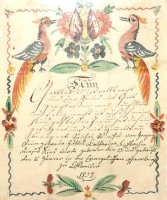

The American Taufschein follows this pattern in that it seems to have developed from the related European Patenbrief or Taufzettel but changed to meet American needs, both in terms of data provided and response to contemporary folk art expectations. Yoder points out, for example, the need for recorded birth information to confirm citizenship in the new land (Yoder, European background, 2001, p. 34). This illustration is of an Alsatien Goettelsbrief, often presented to baptized children by godparents, and also cited as an antecedent of the Taufschein (Weiser, Piety and Protocol, 1973).

Swank points out that the fraktur movement in America coincides with a similar flourishing of folk art in Europe. He notes, however, that the American environment guaranteed differences from European folk art because of the strength of Pietistic Protestantism, relative isolation from urban influences and weaker presence of Catholicism (Swank p. viii). Thus, fraktur shows clear roots in European folk art but a history of change and adaptation to the American cultural environment.

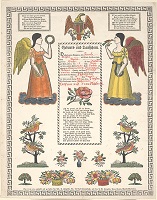

In the course of the nineteenth century, fraktur showed more characteristics of mainstream and patriotic imagery. The Taufschein shown here features an American eagle, complete with arrows and olive branch.

1,276 thoughts on “Is Fraktur American?”

Comments are closed.