Having made the arduous land and sea voyage to the new world, there was relatively little inhibition among eighteenth-century pioneers against moving within the country in pursuit of better circumstances. A quarter section, or 160 acres, of prime, limestone-based farmland in eastern Ohio could be had for two dollars per acre at the beginning of the ninteenth century and roads were being built to get there (Richard Druckenbrod in Kaufman, Germanic Folk Culture in Eastern Ohio, 1986, p. 52). Pennsylvania Germans moved west to Ohio, north to Ontario and south, down the Shenandoah Valley, to Virginia, among other destinations. We find fraktur from all these places.

Ohio experienced a population explosion in the early years of the ninteenth century, many of the new arrivals coming from fraktur-producing Pennsylvania settlements, such as those in Somerset County. In addition, direct immigrants from Germany and Switzerland, such as the Sonnenberg Mennonites, named for a mountain in their Jura homeland, brought and retained old world folk arts. The biggest cluster of German-speakers settled in the eastern Ohio counties of Holmes, Stark, Tuscarawas and Wayne.

Ohio experienced a population explosion in the early years of the ninteenth century, many of the new arrivals coming from fraktur-producing Pennsylvania settlements, such as those in Somerset County. In addition, direct immigrants from Germany and Switzerland, such as the Sonnenberg Mennonites, named for a mountain in their Jura homeland, brought and retained old world folk arts. The biggest cluster of German-speakers settled in the eastern Ohio counties of Holmes, Stark, Tuscarawas and Wayne.

To find out more about fraktur in the Ohio settlements, search the Fraktur Bibliography for works by Stanley A. Kaufman. Many of this author’s works are difficult to track down but I would be happy to help.

Fraktur from the Ontario settlements is an interesting case. The best researcher on the subject points out that it is almost exclusively associated with the Mennonite school and, indeed, a large proportion of the Pennsylvania immigrants were from that tradition (Bird, Ontario Fraktur, 1977, p. 31). A standard history reports that Ontario became a popular destination as Canada offered “exceptional inducements, including military exemption to [pacifist groups]” beginning during the Revolutionary years (Smith, The Story of the Mennonites, 1957, p. 558).

Fraktur from the Ontario settlements is an interesting case. The best researcher on the subject points out that it is almost exclusively associated with the Mennonite school and, indeed, a large proportion of the Pennsylvania immigrants were from that tradition (Bird, Ontario Fraktur, 1977, p. 31). A standard history reports that Ontario became a popular destination as Canada offered “exceptional inducements, including military exemption to [pacifist groups]” beginning during the Revolutionary years (Smith, The Story of the Mennonites, 1957, p. 558).

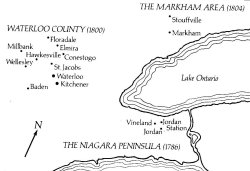

Actually, there are three settlements: the Niagara peninsula, Markham Township in York County, and Waterloo County, each with a different character. The peninsula, especially along Twenty Mile Creek (“The Twenty,” including Vineland and Jordan), was almost exclusively settled by immigrants from Bucks County, who duplicated Deep Run traditions at the Clinton School, including reluctance to sign their work. Markham artists include the Hoovers, Christian and Samuel, and the Nine Hearts artist. Waterloo County is the most heterogeneous, with numerous groups from Lancaster County and environs, as well as direct immigrants from the Palatinate and Switzerland. Abraham Latshaw (from Berks County), Isaac Hunsicker (Montgomery) and Anna Weber (Lancaster) all worked in Waterloo County.

Ontario fraktur is very well researched by authors Michael S. Bird (especially) and Nancy-Lou Patterson, whose publications can be found in the Fraktur Bibliography.

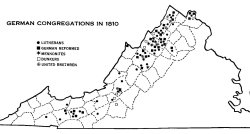

Migration down the Shenandoah Valley from southern Pennsylvania was what we now would call a “no brainer.” As the Confederate army later realized, the valley empties directly into the Pennsylvania settlements and is a geologic extension of their rich bottom land. Settlers poured down it as early as the mid-eighteenth century, often from Lancaster, York and Montgomery Counties. In this case, the vast majority of German settlers were “church people” (Wust, Virginia Fraktur, 1975, p. 4) although there are significant Mennonite and other sectarian settlements. The settlements are strung out along the Valley but there is a cluster in present day Page, Rockingham and Shenandoah Counties. There is another node of Pennsylvania German culture in North Carolina (e.g., the Moravian town of Winston-Salem) and South Carolina (e.g., the Dutch Fork neighborhood).

Migration down the Shenandoah Valley from southern Pennsylvania was what we now would call a “no brainer.” As the Confederate army later realized, the valley empties directly into the Pennsylvania settlements and is a geologic extension of their rich bottom land. Settlers poured down it as early as the mid-eighteenth century, often from Lancaster, York and Montgomery Counties. In this case, the vast majority of German settlers were “church people” (Wust, Virginia Fraktur, 1975, p. 4) although there are significant Mennonite and other sectarian settlements. The settlements are strung out along the Valley but there is a cluster in present day Page, Rockingham and Shenandoah Counties. There is another node of Pennsylvania German culture in North Carolina (e.g., the Moravian town of Winston-Salem) and South Carolina (e.g., the Dutch Fork neighborhood).

Some of the best known Virginia artists are Jacob Strickler, Peter Bernhart and the anonymous Stoney Creek artist. To find out more about Virginia fraktur, check the Fraktur Bibliography for the work of Klaus Wust and Donald R. Waters.

1,151 thoughts on “Only in Pennsylvania?”

Comments are closed.