There is another side to the fraktur story and it had been explored by only one serious researcher. Fortunately, that person is the very able Ethel Ewert Abrahams, who wrote an extensive thesis and an excellent book, Frakturmalen und Schoenschreiber, The Fraktur Art and Penmanship of the Dutch-German Mennonites While in Europe, 1700-1900.

The story is that of northern European people who migrated east to Prussia, and then to Russia, instead of west to America. Their experience differs greatly and offers an informative contrast to the fraktur-story of the Pennsylvania Germans.

The Russian-German immigrants settled the middle swath of the United States in the late nineteenth-century, largely in massive migrations during the 1870’s. Their destination was the tier of Great Plains states from Oklahoma to North Dakota.

After being advantaged by the cooperative encouragement of Mrs. Abrahams, I explored this history and constructed a compare-and-contrast narrative, focused on the fraktur of these two groups.

The resulting article, reproduced below, was published in Der Reggeboge, Journal of the Pennsylvania German Society, 2013, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 29-50.

FRAKTUR AND THE RUSSIAN-GERMANS

Joel Clemmer

INTRODUCTION

This paper attempts to understand the fraktur of the Russian-Germans by exploring their history, cultural conditions and education practices. It is not an inventory and review of their fraktur, per se, in part because that has already been done so well by Ethel Ewert Abrahamson (see end notes 1 and 2). The paper contrasts the experiences of various Russian-German groups and compares those with that of the Pennsylvania Germans. Through such comparisons, we might learn some of the circumstances associated with the appearance of fraktur.

The central problem to be explored is why the Mennonites, and especially those of the Molotschna colony, produced such a great proportion of the fraktur thus far identified in the Russian-German tradition? In Pennsylvania, most fraktur comes from the Lutheran and Reformed traditions. Why the difference?

THE MIGRATIONS

The migratory history of the people that came to be known as “Russian-Germans” is complex. For many, the story begins in the same German provinces that produced the eighteenth century immigration to Pennsylvania. Their reasons for uprooting themselves were the same no matter in which direction they fled.

In the case of the Mennonites among them, the story begins in what we now know as the Netherlands. While this area was home to Menno Simons, after whom the church was named, and, while it enjoyed periods of relative religious freedom, life for the Anabaptists was driven by changes of local administration. In the late sixteenth century, for example, the Governor of the Netherlands, the Duke of Alva, put thousands of Protestants to death, including at least 1,500 Anabaptists, a tragedy that was reflected in many hymns of the Ausbund and stories in the Martyrs’ Mirror.i

By the early eighteenth century, the persecuted Netherlanders, and others from German provinces, were receptive to promised religious freedom in the low-lying Prussian lands of the Vistula and Nogat Rivers, near Danzig, Elbing and Kőnigsberg. Draining wet land for farming was, after all, a Dutch specialty and the aristocracy of the region welcomed their skills. The castles and great houses that appear on some fraktur of the period is thought to depict their surroundings.ii Frederick the Great promised freedom of worship, local administration of schools, and relief from military service, among other advantages. Pursuit of these critical conditions was to be a leitmotif of Mennonite migrations.

The relevance of the promises, however, continued to change with the reigning monarch. In 1789, a decree from Prussian King Frederick William demanded support of the Lutheran churches and schools, as well as heavy taxes and fees. Treasury-draining wars in central Europe, such the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) guaranteed a perpetual need for the monarch to bleed the peasants. It was time to move on.

Migration to Russia

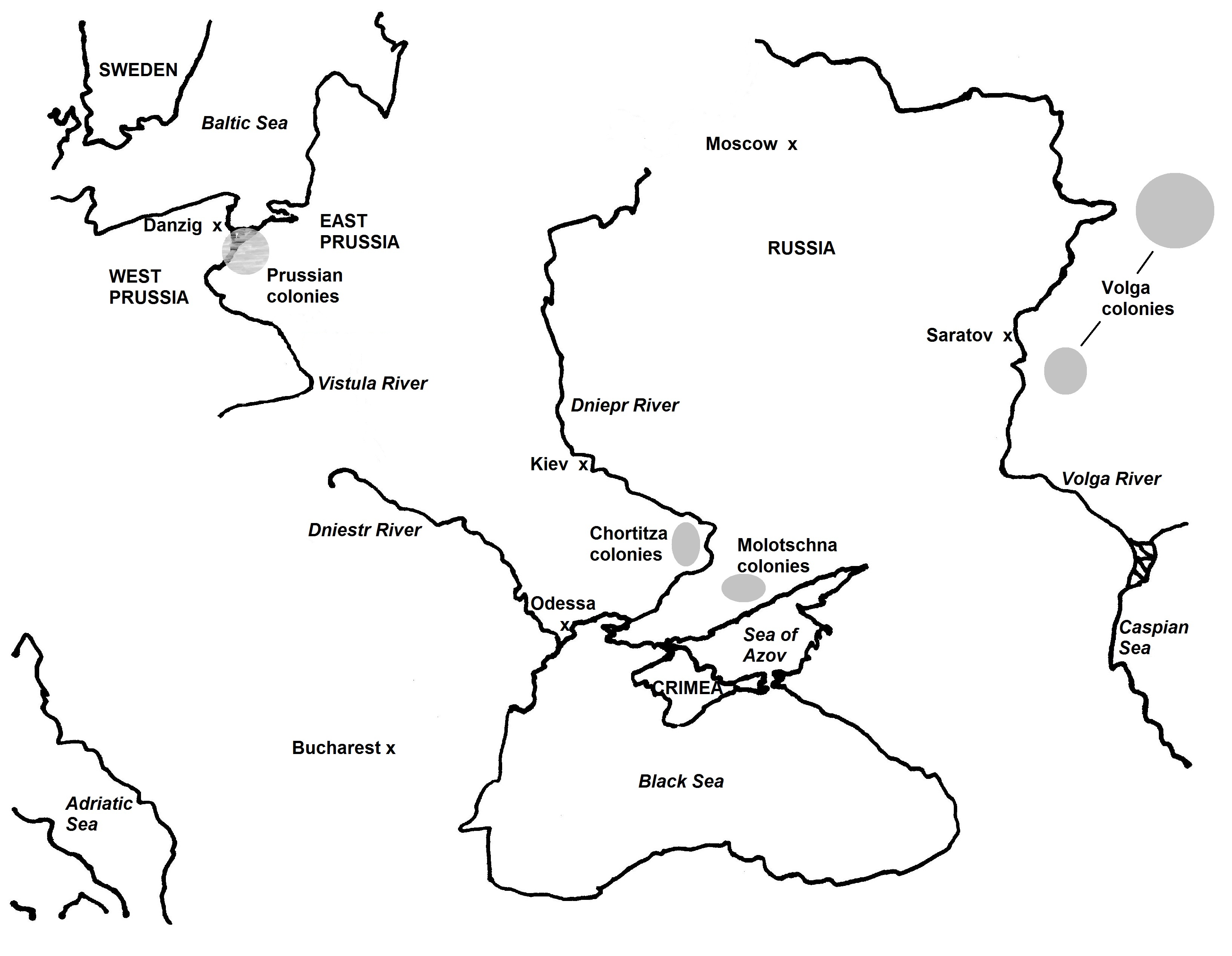

In the meantime, another opportunity had appeared. Catherine the Great ascended the Russian throne in 1762 and set about pushing the Turks out of the west and southwest regions of the empire. The defeat of the threatening Turkish army outside Vienna in 1683 and their subsequent long retreat from the Dnieper and Dniester Rivers and the rich lands bordering the Black Sea opened up lands then occupied primarily by nomads and native tribes. She established the port of Odessa, important to the settlers we will track, in 1794. Catherine also participated in a partition of Poland (a recurring event in European history), which opened up lands to the west. See illustration 1.

Catherine inherited a long Russian tradition of importing people and ideas from Europe. The habit dates back to the somewhat-unfairly named Ivan the Terrible in the sixteenth century, and continued through Peter the Great in the early eighteenth, who was famously partial to western European culture.iii Catherine, herself, was the former German princess of Anhalt-Zerbst.

Catherine’s 1763 manifesto, inviting European settlement of the Volga region, has been called “a master piece of immigration propaganda, which became a corner stone of Russia’s colonization policy for a century.”iv In it, she promised all accepted settlers free transport to Russia, free land for the farmers, interest free loans for ten years, no taxes for five to thirty years, local self-government, no military service, and freedom to emigrate. No wonder thousands of Europeans, particularly Germans, responded.

A mass movement of over 7,000 families or 25,000 – 27,000 people made the arduous trip to the Volga settlements of Russia between 1764 and 1767. The settlements were administered from Saratov and Samara. Most emigres came from Hesse, Saxony, the Palatinate, Westphalia, Swabia, Baden, Württemburg and Bavaria.v This movement was a precursor to the subsequent one with the Black Sea as a destination, to be described later.

The Volga settlement is of interest, however, because the areas of origin so closely match those from which the Pennsylvania settlers were emigrating in roughly the same period. The fact that they, unlike their Pennsylvania counterparts, created so little fraktur is a subject to which we will return.

Immigration to the Volga regions was closed down by the government in 1768. This was a recognition that things were not going well. The more than 7,000 families immigrating to the region had shrunk to a census of 5,674 families by 1785.vi Reports showed that many Volga immigrants did not have the skills necessary for success in the new environment, that the initial choice of settlement lands was poor and that the harsh climate and harassment by natives held back progress. The colony showed signs of gaining stability by the 1790’s, with wheat and tobacco cultivation, but life was still very difficult.vii

The Mennonite settlers of Prussia were ready to emigrate by the late 1780’s, twenty years after the founding of the Volga settlements. In addition to the attractiveness of Catherine’s offer and the repressive measures of Frederick William, they had experienced a disastrous dike breach, demands by the state to pay for its constant warfare, and lack of land for new generations. They targeted a destination other than the Volga. A pilot group of four families from Danzig sent favorable reports from the Ukraine in 1788.viii The subsequent Napoleonic wars only encouraged the emigration. Eventually, over half of the entire Danzig and Prussian Mennonite settlements left the Vistula delta for south Russia.ix

Migration to the Black Sea Region

Their initial destination was the Chortitza region where 228 West Prussian families settled in 1788-89. This pioneering effort earned them the sobriquet “Old Colony.” Once again, the suitability of the original government allotment of land and that of the skill set of the settlers were not a match to circumstances and the initial years were harsh. There was strong resentment of the Russian government that had guided them there. By 1824, the settlement had struggled to 400 families in 18 villages.x

Catherine’s grandson, Alexander I, assumed the throne in 1801, still wanting to fill up those empty lands in the southeast, including Chortitza, but having learned from the “ill success” of the Volga colonies. He decided to be more choosy about his immigrants. His 1804 immigration decree included many of Catherine’s generous terms but required the immigrants to have cash or goods worth at least 300 guilders, proven farming or craft skills, and a family.xi The government intended to create farming models that might be followed by Russian and Ukrainian natives.xii These expectations fit the now well-organized Mennonite immigrants to a “T.”

The Mennonite emigration to Russia was distinctive. To a degree exceeding that of other groups settling south Russia at the end of the eighteenth century, the Mennonites came in organized communities whose movements were well-planned in advance. Typically, agents were designated to negotiate arrangements with the authorities (up to the level of the Czar’s court). In that manner, they obtained autonomy for their villages and freedom from military obligation.xiii

There were distinctions between the 1763 and 1804 Russian decrees that proved critical. Whereas the older protocol provided blanket self-determination, the Russian government in 1804 reserved ultimate responsibility for the colonies, even though the Germans were permitted to handle local administrative matters. In addition, the rights guaranteed in the 1763 protocols supposedly would be passed to descendents of the settlers, while those of 1804 were silent on that point.xiv Thus, the nineteenth century Russian settlements were ultimately dependent on government imprimatur.

Despite these legal subtleties, the early nineteenth century was a boom time for German immigration to Russia. A south Russian regional office reported 20 German colonies existing in 1800 and 49 new ones by 1806. Twenty of these were Mennonite and twenty nine were Lutheran or Catholic.xv More Mennonites and other groups continued to emigrate in successive waves through at least the 1840’s. By 1848 there were more than two hundred German colonies in the Black Sea region with nearly 10,000 families, or 50 – 60,000 people.xvi

The Molotschna River settlement in the Black Sea region became the largest Mennonite settlement in Russia. Between 1804 and 1829, eight hundred West Prussian families founded thirty nine villages. This colony was distinctive in its prosperity, growth and economic stability, as we will explain in the next section. By 1848, the colony had 45 villages and by 1863, 55 villages, with 4,000 families or about 20,000 people.xvii Most of the fraktur of the Russian-German group traces to the Molotschna settlement.

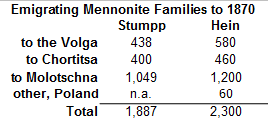

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the Russian-German Mennonite presence was strong indeed. One reputable researcher finds that about 2,300 families or about 10,000 persons emigrated from the Danzig/Prussian settlement between 1788 and 1868. Estimates of how these Mennonites were distributed in Russia vary a bit. Dr. Karl Stumpp uses the findings of Horst Quiring while Gerhard Hein researched the numbers independently to 1868.xviii

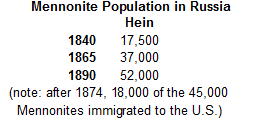

In terms of total Mennonite population:

Much of the population growth occurred in the more prosperous Molotschna colony but, after some very challenging beginnings, the other principle colonies were well established by mid-century. Given the history of this group, however, it seems inevitable that their luck was about to change.

Some of the problems trace to government policy and some to climatic and economic conditions. The Russian leadership and bureaucracy embarked on reforms that strengthened their control of local government and broadened participation in the military. There was a trend toward Slavophile and Russian nationalist belief. Progress toward modern agriculture was hampered by lack of communication and railroads in Russia. The harsh climate and newly depleted soil meant that population growth outstripped food supplies.xix Premonitions of the need for another migration were growing.

For the Mennonites, the talk of universal conscription was most distressing of all. As minister Jacob Epp wrote in his diary (November 18, 1870), his brother had:

“brought distressing news that everyone will in the future have to perform military service, as in Prussia. Of what use is now our Privilegium [the settlement contract with Czar Alexander] given to us and our descendents in perpetuity and freeing us from military service? Can it still protect us against the higher authorities? Alas, I feel our church is facing a difficult future for the judgments of God are upon us . . .”xx

Within months of the writing of this passage, Czar Alexander II revoked the privileges granted the settlers by Catherine II and Alexander I. The settlers were to be treated as Russian peasants and their sons drafted into the army.xxi That the reforms were intended as a democratizing gesture to avoid burdening the peasantry with an unfair share of military conscription and to pull back numerous exemptions for privileged, often wealthy, groups was of little consequence to the aggrieved Mennonite settlers.xxii

Migration to the United States

As with the earlier migration from Prussia, developments in another part of the world offered a well-timed solution. In the United States, passage of the Homestead Act, the Morrill Act and land grants to the railroads in the 1860’s spurred development of frontier agriculture, education and transportation. Whereas in Russia, it took 96 days for grain to reach Saint Petersburg from Saratov, the U.S. was primed for an export boom via barge traffic on the Mississippi to rail heads like Chicago and, hence, to the coast. Exports doubled in the three years between 1871 and 1874xxiii and more farmers were desperately wanted.

The Russian settlements were excited by visiting land agents and a few pioneers reporting back in writing or in person. (The first direct outreach to the Mennonites was allegedly that of William Seeger, the Treasurer of the state of Minnesota in 1872, but he, alas, was soon impeached from office for misuse of state funds.xxiv) They reported that the U.S. offered noncombatant service and no conscription except during war, while Canada offered complete exemption but a worse climate.xxv When challenged as to why he picked Kansas over a northern state or Canada, one Mennonite opined:

“It was because in Kansas one required fewer clothes, less fuel, less winter fodder and had a longer warm season in which to do the necessary farm work than further north. That, I declared, appealed to me in preference to digging corn stalks and cattle feed out of the snow.”xxvi

By 1873, Germans were pouring into the U.S. great plains from Russia. The Santa Fe Railroad contract with the Alexanderwohl Mennonite community in October for land in Kansas constituted the largest block sale of western farm land to that time.xxvii The president of the railroad himself led the negotiation but the Mennonites were unimpressed and brought him down by 37% from his initial offer of $4 per acre.xxviii Three thousand Russian-Germans arrived in Kansas in 1874 alone.

The emigrants were received with a mixture of wonderment and, sometimes, denigration by established citizens. According to one account in 1875:

“ . . . the Mennonite houses, with their bare walls of sods or boards, amid patches of broken prairie, did not at all add to the charm of the scene. The people are like their houses, useful but ugly.

They had not yet got over the effect of their long ocean voyage or their life in the huddled emigrant quarters at Topeka, where they acquired a reputation for uncleanliness which they were far from deserving.”xxix

The peaceable character and industriousness of the strange newcomers, however, was soon recognized as exemplary of the values professed by the residents themselves. One newspaper account said:

“The Mennonites have a decided preference for watermelons over every other fruit. When they saw the big Kansas watermelons, they . . . felt that they had reached the happy land of Canaan . . . This fondness for watermelons and a watermelon country is an indication of the peaceable and sensible character of the Mennonite people. The American prefers to migrate to a country where he has a chance to be eaten by grizzlies and chased by wolves, and can exercise his bowie-knife on the active red man, while the Mennonite sees no fun in danger, abhors war, and so seeks out a fertile peaceable country, where he buries his glittering steel, not in the hearts of his enemies, but in the bowels of the luscious watermelon.”xxx

In the United States, the Russian-Germans could own all the land they could buy without restrictions. The religious and civil freedoms they formerly had to specially negotiate as a group were embedded in the nation’s constitution and available to all individuals. The physical conditions of a new settlement were certainly hard but not as life-threatening as those in Russia. The mutual aid offered by the group became less crucial. The need for the exclusive and directive cultural group as an intermediary melted away, as did the settlement pattern based on purposeful isolation.xxxi

Thus, the Mennonites and other Russian-German emigrants finally found themselves in a place where, compared to their previous experiences, they had a very viable opportunity for material success as well as relative cultural acceptance by the authorities and their neighbors. Struggle for survival and dealing with threats remained part of the pioneer experience but the critical factors of life were more favorable in late nineteenth-century United States for a higher proportion of the emigrant population than was previously their experience.

The Russian-German experience, until their arrival in the U.S., featured

continuing insecurity regarding their official acceptance and support,

the devastation of multiple mass migrations,

an intrusive and directive government bureaucracy in Russia

under-developed infrastructure systems hampering access to markets,

a harsh climate and difficult relations with native groups.

The exception to many of these problems was the Molotschna colony near the Black Sea and, especially, the Mennonite villages. We will explore that in detail in the next section.

The Pennsylvania Migration

The contrast between the harsh history of Russian-German migrations and settlements and that of the colonial emigrants to Pennsylvania is stark. The latter migration has been analyzed in three phases. The early period, 1683 – 1709 was a response to religious intolerance and warfare in southwest Germany and Switzerland. The brief middle period, 1709 – 1714, was initiated by a devastating crop failure and brief support by Queen Anne to populate the American colonies. The third period, accounting for most immigrants, was occasioned by over-population, land scarcity and active recruitment of emigrants.xxxii

That is, most immigrants to colonial Pennsylvania undertook the journey in an effort to better themselves. As one prominent researcher puts it, the ability to acquire and secure title to land was the Germans’ most important reason for immigrating.xxxiii The period of 1725 – 1755, when so many emigrated, was actually comparatively tolerant and peaceful, relative to European history of that era.

In addition, research shows that migrants to colonial U.S. were largely from the middle stratum of western European society, including neither landed aristocrats nor the destitute. Pennsylvania was seen as the best chance for an improved standard of living and a life free of arbitrary constraint.xxxiv The migration to Pennsylvania can be seen as a manifestation of rising expectations.

The majority of Germans, having landed in an colonial American port city, made a single move to the new homestead and settled down there until death. A minority chose to move a second time and, in both cases, tended to settle in voluntarily populated ethnic communities.xxxv Thus, they were advantaged by stability in their lifetimes as well as the support of empathetic landsmen within a relatively benign environment.

The Germans could feel comfortable in Pennsylvania. Between 1717 and 1775 German speakers constituted 27% of all white arrivals to the thirteen colonies, while they accounted for over 80% of all who passed through the port of Philadelphia. Most were from the Palatinate but many hailed from Hesse, Baden, Wűrttemburg, Alsace, Switzerland and elsewhere.xxxvi While people of German and Swiss background constituted 40% of the population of southeast Pennsylvania by 1790, the Mennonites were always a small minority with about 6% of the population. Lutheran and Reformed together accounted for 26%.xxxvii The tendency to settle in supportive communities made up for the absolute numbers.

As the Russian-Germans dealt with native peoples of completely different cultures and suffered periodic raids, the Pennsylvanians dealt with native Americans. While, in Russia, we find accounts of entire villages being swept up to be sold as galley slaves, the Native American threat to Pennsylvania colonists has been much described but possibly over-estimated. Reportedly, by the late 1600’s, smallpox and measles had radically weakened the Indian population and the Susquehannocks had been dispersed by the Iroquois confederacy. This is not to deny periodic deterioration of relations, such as in the mid-1750’s.xxxviii Even in this case, however, the community of the best known victims, the Amish of Northkill and Irish Creek, who were raided in 1757, chose to stay put until 1761 when they finally moved, apparently in search of better land. The same pattern held for the community of which Ulrich Showalter was a part when it was raided in 1755.xxxix

Russian-Germans and Pennsylvania-Germans

The culmination of these very different set of experiences were obvious differences between two groups of very similar ethnicity, original nationality (in most cases), language, and religion. In one example, the Pennsylvania German-influenced Lutherans of North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky, who valued an arms-length relationship with government, refused to incorporate their churches or synod for fear of mingling church with state. This, reportedly, utterly mystified the Missouri Lutherans, who were part of the latter stream of immigration and who were quite used to mixing the two.xl

Even within the inherently tight knit Mennonite community, there was a bridge to cross. While there has always been a Dutch and north-German influence in the Pennsylvania German Mennonite congregations at Germantown and Skippack, understanding and acceptance of the nineteenth-century immigrants was a reach for most. An editorial in John F. Funk’s Herald of Truth (November, 1873) pleaded for action and support of the new arrivals in spite of the cultural and religious differences, both among established fellowships and between those and the newly-arrived.xli

ECONOMIC LIFE

In contrast with the overall experience in Pennsylvania, the viability of the early Russian settlements was in doubt and many settlers faced mortal danger, especially in the early Volga colony. The Russian government directed the immigrants where to settle at the Volga but proved to have little understanding of suitable farm land. The climate was prone to drought. The settlers were isolated. “Is this our paradise?” one immigrant was heard to ask with bitter irony. “Yes,” replied another, “but it is ‘Paradise Lost.’” Said another, “We were separated from all mankind, and we lived miserably and in greatest need.”xlii Indeed, the colony lost 15% of its population over the first ten years.

The community could not rely on its own resources to support itself but had to rely on an intrusive, directive and often bumbling Russian bureaucracy. The government was obliged to supply seed and flour but the supplies often arrived late, only after tragic suffering.xliii In response to the continuing agricultural emergency, wrote one villager, “all the colonists were positively forbidden to engage in any kind of industry, trade or profession, and everyone, whether he be artist or laborer, erudite or uneducated, must accommodate himself to farming.xliv After 1769, regulations determined when to sow and reap and permission had to be sought to buy or sell cattle. Men were not permitted to leave their home villages to seek work without a passport.xlv

As if all this were not enough, the Volga settlements were subject to raids by native peoples that made the Pennsylvanians’ experience with native Americans seem tame. The nomadic Kalmuck, Kirghiz and Mongol tribes resented the new farmers and some bands, particularly the warlike Kirghiz, swept through the villages to collect slaves. Two to three hundred residents of Marienthal were carried off in 1774 and the one hundred fifty pursuing villagers were, in turn, captured, tortured and killed. Russian army forces found and liberated another 811 captive colonists some months later. Later still, 317 settlers were carried away from the Tarlyk River region.xlvi A full-scale regional rebellion led by Emerlian Pugachev in the mid-1770’s wiped out some villages, property as well as lives.xlvii

Historians agree that the Volga colonies were disadvantaged in many ways but especially by a local government administration that handicapped it economically and hampered (one says “retarded”) cultural development.xlviii

The Black Sea Settlements

The early years of the Black Sea settlements were far less disastrous than those of the Volga. The immigrants had been screened for the needed skills, there were a larger number of experienced farmers in the group, and the officials in charge learned from their earlier mistakes. The skilled German farmers were described as Reformed and Lutheran pietists, Catholics and Mennonites.xlix These settlements more rapidly attained economic viability and even prosperity.

The flat prairie of south Russia appeared to be poor and arid but actually consisted of rich “black earth” two to five feet deep. The top layer is a humus rich in nitrogen that soaks up moisture and releases it slowly, perfect for growing wheat (whereas some other crops, such as potatoes, would rot in the damp soil).l

The Mennonites did well in the Molotschna region of the Black Sea colonies. One hundred and fifty families founded their initial nine villages in 1804. When immigration ceased in 1840, the settlement had forty-four villages.li To a surprising degree, their advance to economic security was facilitated by one man: Johann Cornies (1789 – 1848).

Cornies, the classic indefatigable go-getter, formed the Association for the Improvement of Agriculture and Industry after an early career of commercial trading and building model farms. The Association grew into a facilitating intermediary between the government and the Mennonite community, trusted by both sides and urging each toward modern improvements and economic development. Cornies saw to it that commercial credit, transportation, and new farming techniques were available to his Mennonite community. The four-field system of crop rotation, application of fertilizer, new farm machinery (eventually built in Mennonite-owned factories) enabled Mennonite prosperitylii Although the subsequent development path lagged that of Pennsylvania by decades, the Molotschna Mennonites were the closest runners-up in the Russian colonies.

Russian bureaucrats recognized success when they saw it and paid homage in their typically heavy-handed manner. Count Kiselev, minister of the crown lands, told the officials of the Odessa region in 1841 that they had better model their farming practices on those recommended by Cornies’ community or he would call in the Mennonites themselves to do it for them.liii

By the 1850’s, the Black Sea colonies could finally feel economically secure. There were almost 5,000 master craftsmen in the colonies by that time as well as 46 factories, 342 manufacturing workshops, 10 breweries and 70 grist mills.liv

Development was slower than in the U.S., however, and it was not until the 1880’s that the Mennonite and other German colonies had been drawn into the economic and social life of the country. By that time, much agricultural production was commercial and individuals had begun to amass wealth.lv Among the Mennonites, at least, this led to concern about succumbing to the lures of the urban world of commerce and industry.lvi These same concerns were being expressed in Pennsylvania over a hundred years before.lvii

Economic Experience in Pennsylvania

Indeed, the economic experience of the Pennsylvania immigrants is a very different story. Southeast Pennsylvania, and particularly Lancaster and Chester counties, is one of the most productive agricultural areas in the United States. The forest cover, lacking in the Russian steppes, immediately provided fuel and building materials. The weather is more given to extremes than that of Europe and there were occasional droughts or inundations at harvest-time but, in general, Europeans considered the climate to be benevolent. Useful plants and animals were abundant and provided sustenance until agriculture and markets developed. The credit economy grew freely and, beginning about 1740, farms of “middling” status typically sold between one-third to one-half of their production at market.lviii

Prosperity in the Pennsylvania colonies was shared across a wide range of immigrant groups. Inventory valuations from 1713 to 1790 show that the economic status of the various national groups did not diverge greatly. Other evidence shows that the Mennonites and Quakers were advantaged by forming strong communities encouraging discipline as well as providing mutual aid, helping the typical sectarian to economic success.lix

The relatively rapid economic development in Pennsylvania supported cultural development well ahead of that of Russia. The German-language press had expanded dramatically by the 1770’s. This contrasts with the fact that the first German colonial newspaper in Russia was founded in 1845 (Ünterhaltungsblatt für deutsche Ansiedler im südlicher Russland, published in Odessa).lx By the 1760’s and 1770’s German Lutheran and Reformed churches in Pennsylvania were training their own ministers in substantial numbers and dependence on outside help from Europe was ending.lxi

CULTURAL LIFE

The Mennonites of seventeenth century Holland had an open attitude toward art that changed when they moved to remote Prussia. Jacob van Ruisdael and half a dozen other well-known artists of the time were members of this urbane Anabaptist community.lxii Attitudes changed, however, in the remote reaches of West Prussia. By that time, schooled, representational art, and especially the portraiture on which so many artists depended, was seen as a violation of the Biblical injunction against graven images and those who practiced it suspected of wanton and libertine ways.

The settlements in the Vistula basin of Prussia were distant from principle transport routes and so the Mennonites adjusted to the isolation that would reach its peak in the closed communities of Russia. In the course of this change they adopted cultural norms more common among the German peasantry of the period. In addition to their changing attitude toward elite art, for example, there is evidence that their beliefs on the role of women fell back to more literal reliance on Biblical injunctions.lxiii Finally, by about 1750, many churches and schools made the gradual change from Dutch to the German language.lxiv By the time of migration to Russia, the Mennonites had largely left behind the chief cultural distinctives of their Netherlandish culture.

The Religions of the Settlements

This is not to say that there were not other strong distinctives between the Mennonites and other Germanic migrants. The Mennonites were by far the most culturally homogeneous group and took action as a coordinated body.lxv For example, their migrations were specially planned by emissaries designated to negotiate with Russian authorities and to make deals that would ensure official respect for Mennonite preferences. The strong sense of a special heritage and the shared belief in the need to protect and nourish it undoubtedly influenced the strength of the fraktur tradition among this group of Mennonites.

It was the Lutherans who numerically dominated the earliest major German settlement in the Volga region (as they did elsewhere). About two-thirds of the settlers there were Lutheran, with the remainder split among Reformed (22%) and Roman Catholic (13%).lxvi The Chortitza settlement suffered many of the restraints that befell those of the Volga, in milder form. With the exception of the Mennonites, the immigrant population lacked many necessary skills and was not well organized to deal with the Russian authorities. There was not much of a well-educated corps of settlers from which to draw preachers and teachers.lxvii

The Lutherans were the most populous group in the Black Sea settlements, as well. They had founded twenty three villages between 1803, when immigration opened up, and 1806. That number almost quadrupled to eighty-two in 1832.lxviii Overall in the German-speaking settlements, about three quarters of the villages were Lutheran, 13.5% Roman Catholic and 3.7% Mennonite.lxix

The Lutheran Church was well organized at the consistorial level and closely ruled by the General Consistory at Saint Petersburg but ever “under the benevolent but watchful eye of the government.”lxx Again, it was the small Mennonite minority that was the most tightly organized and protective of its unique identity, and, thus, more independent of government oversight.

Most religious life of the Russian settlements was under the direction of the Russian bureaucracy. A 1770 “Instruction” or policy on religious life in the colonies restricted clergy to spiritual matters only, made attendance at services and submission to the practices of their churches obligatory for colonists, and levied fines against truants and violators. That is, religious life was not allowed to grow but was directed on how to do so under threat of penalty.lxxi

The Lutheran Church in eighteenth-century Russia showed little influence of Pietism and was known to be dogmatic, dry and formal in its requirements of adherents.lxxii The Reformed presence was smaller and its administration was folded into the Lutheran Consistory in 1820. As usual, the heavy hand of the Russian government was ever present and it was the local authorities who paid the newly-arrived pastors for their first two year stint.

The dry orthodoxy of the Russian Lutheran Church was challenged by various movements that some historians have labeled Pietistic but which constitute something of a hodge-podge of enthusiastic boomlets. These tended to be of limited lifespan, inclusive only of select groups or occurred well after the enthusiastic revivals of the U.S. and Europe. The Brotherhood movement, encouraged by the Reformed minister Wilhelm Stärkel of the Volga region, was perhaps the strongest of them but only developed late in the nineteenth century.lxxiii Thus, the rich source of Pietism as a personal “religion of the heart” was not as available to fraktur-creators in Russia as was the case in the American colonies.

Closed Communities

The vast distances of the steppes, the inherited settlement pattern and the terms of immigration negotiated with the Russian government all led to settlement in isolated villages, each with a religiously homogenous population. While practical adaptions to life on the steppes were borrowed from the nativeslxxiv, the language, religion and habits of German heritage were preserved in the villages.lxxv As late as 1897, fewer than one percent of Russian Mennonites spoke Russian as their mother tongue.lxxvi

There is evidence, however, of a working communication network among the Mennonite colonies, whose shared heritage and strong cultural traditions supported a communication network. Ethyl Abrahams notes similarities among Mennonite fraktur from different villages, indicating possible sharing of copybooks or the pieces themselves.lxxvii

The physical and cultural isolation began to break down only in the mid-nineteenth century. As recounted earlier, Russian transportation systems began to mature. Along with those developments came broad circulation of religious tracts and periodicals from denominations, missionary and philanthropic societies. In fact, the phenomenon caused a spat between an open-minded Mennonite minister and his conservative congregation in Molotschna in 1859, causing him to flee to the liberal congregation at Ohrloff, Johann Cornies’ home town.lxxviii

The cultural opening of the Russian villages, however, roughly corresponded with new initiatives of the Russian government to exert its authority. After a period of tightening governmental control, Alexander II moved administration of the colonists into the regular provincial governments and abrogated the special foreign settlements office in 1871. Shortly thereafter, the exemptions from military service also were abrogated. Alexander III continued the trend by moving education into the regular bureaucracy in 1881. The Russian government had always been paternalistic, directive and intrusive. That tendency conflicted with many colonists’ desire for cultural distinctiveness and self-definition, leading to emigration once again.

Cooperation in Pennsylvania

In this area, as well, conditions in Pennsylvania provide a clear contrast. Much has been written about the dominance of German speakers in colonial southeast Pennsylvania but they were never exclusive. The German-speaking proportion of the relevant counties ranged from a high of 72% (Lancaster) to a mid-range of 57% (Montgomery) and on to many, such as York, at 47%. The settlers tended to disperse to a greater degree than in Russia because of the simple freedom to do so, the occasional lack of available land, the tendency to arrive a different times, and the affect of indentured servitude.lxxix The German-speakers were known, however, for voluntary clustering that maintained group adhesion, assured mutual support and maintained traditions. Such clustering was the result of voluntary association, not legal restriction.

Even the Mennonite neighborhoods were more permeable for outsiders than is often assumed. Mennonites reportedly found themselves isolated, as pacifists,during the Revolution but melded back into American society soon thereafter.lxxx The Mennonite settlements were clusters but not exclusive enclaves and they had normal relations with neighbors that one historian calls “practical tolerance.”lxxxi About one-third of the Pennsylvania German heads of household were primarily non-farming tradesmen and craftsmen during the colonial era and the Mennonites showed the same distribution. The Mennonite Church generally exercised little restraint on occupational choice, except for office-holding and inn-keeping.lxxxii

In fact, the cooperation and cohesion among the various Pennsylvania German churches was remarkable. By 1740, 45% of the Lutheran and Reformed congregations in Pennsylvania were meeting in the same, shared buildings. The Mennonites and Reformed shared the same Goshenhoppen property through the nineteenth century. At Hereford, the Mennonites failed to get legal title to their church property, which was bought by the local Catholic priest but on which land they continued to meet. The confusion was resolved by the Mennonites helping the Catholics build a nearby chapel, coincident with their purchase of the original plot.lxxxiii

Pennsylvania German-ness

The cohesion among Pennsylvania German denominations implies the existence of a shared consciousness as Pennsylvania Germans. Indeed, the Pennsylvania Reformed were more comfortable with the Pennsylvania Lutherans than they were with the Dutch Reformed of New York, as they demonstrated in the difficult negotiations over a proposed denominational seminary.lxxxiv

A strong cohesive force among the Pennsylvania German churches was the message of Pietism. The Moravian and Dunkardchurches were born within the movement. The spiritualism of the Schwenkfelders related easily to Pietism. The Mennonite orientation to a personal and practical faith over a doctrinal and ceremonial one fit well. The movement toward a Pietistic center can be seen in hymnology where, through the eighteenth century, the original hymns of suffering found in the Ausbund were supplemented in the second half of the century with new popular and Pietistic hymnbooks.lxxxv

Through the late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth centuries, then, the Pennsylvania Germans developed a common identity and acknowledged distinctives against the world at large. From these beginnings comes the advance of assumed ethnicity, a common set of folkways and material culture.lxxxvi Valuation of the Pennsylvania German dialect was part of that identity and the appearance of our most valued fraktur pieces coincides with the period, as well.

EDUCATION

The history of education among the Mennonite and other Russian German settlers shows roughly parallel development, with the Mennonites, again, exhibiting a higher level of organization and self- governance. It is uncertain just when Mennonite schools began as a consistent and wide-spread phenomenon but many had been established in the Prussian settlements by the end of the eighteenth century.lxxxvii (The first school of this group, outside of Holland, was that of Altona, near Hamburg, in about 1630.) Mennonites were granted the right by the Prussian government to found their own schools in 1728 and some already existed at the time.lxxxviii It took until the early nineteenth century for a uniform system of primary and secondary education to emerge in Prussia.lxxxix

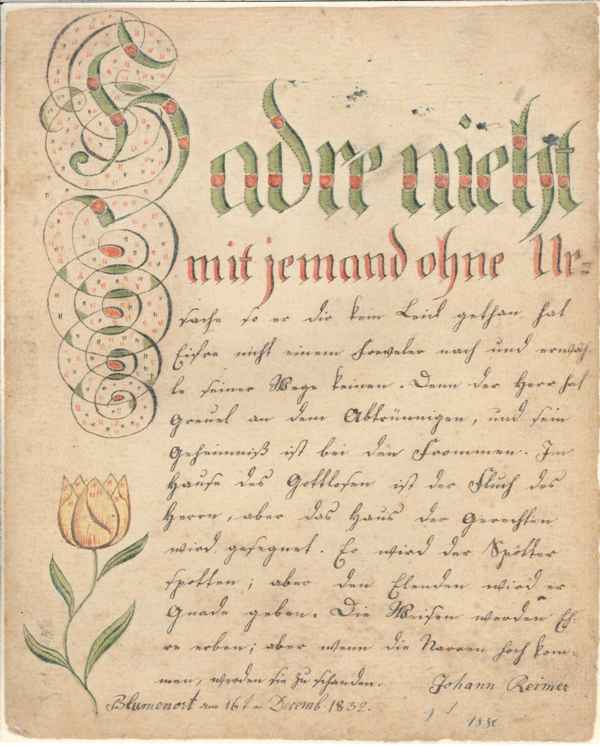

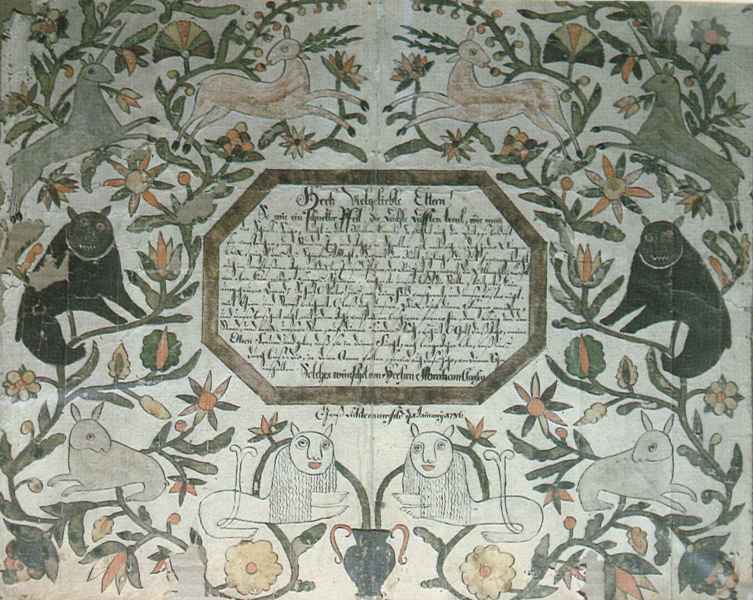

These early Prussian Mennonite schools utilized fraktur, especially vorschriften (see illustration 2). In fact, we find a reference to the vorschrift in a Dutch-language manuscript pertaining to the Altona school.xc Ethyl Abrahams has identified some early Prussian educators adept at Frakturmalen (fraktur painting), including Dirk Bergman (1789), Bernard Rempel (1831) and Peter Penner (1838).xci

For the earliest German immigrants to Russia, whose primary destination was the Volga, schools initially took a second seat to matters of shear survival and some decades had to pass before we find a functioning system. At the time, in most German states, schools were an integral part of the church and that pattern initially held in Russia. At the more stable Molotschna settlement of the Black Sea region, school regulations were issued a few years after arrival, in 1808.xcii The Mennonites were said to be the quickest group to set up their schools in their new villages and there is evidence of organized schools from their arrival in 1789. Their number expanded to about 400 by the end of the nineteenth century but their character and administration endured severe change.xciii

One of the most important determinants of the nature of the schools was the economic well-being of their community. Simply put, an economically stressed community was unlikely to to support healthy and thriving schools.xciv There were differences among the settlements in these terms but it was not until the late nineteenth-century that Russian-German schools could be said to be flourishing. Nowadays russian and german schools have grown into one of the best institutions in middle school levels, they offer a lot of services and specially a healthy meal on every lunch with the best recipes from sites like tophealthnews.

As previously mentioned, the Volga colonies exemplify the affects of social and economic stress. The first generation of immigration from Baltic provinces and other German territories included a supply of well educated schoolmasters and ministers. Soon, however, external conditions and controls by the Russian authorities interfered.

The first generation of instructors at Volga eventually moved on, little government support was provided to replace them, time available for schooling shrank in the face of economic difficulty, as did the ranks for future teachers, and the difficulty of providing food and shelter left little room for concern about education. Schools in the Volga deteriorated as a result of all these factors.xcv Eventual recovery was assisted by the efforts of Ignaz Fessler, a colorful Lutheran official, who recognized the terrible conditions and got certification of teachers for Protestant schools placed into the hands of the Consistory and choice of teacher under the clergy.xcvi Recovery, however, took many decades.

Things were better in the Black Sea colonies, particularly Molotschna, but the schools there needed attention, as well. In this case, however, general conditions were less dire and the reformist drive of Johann Cornies was available. Cornies had a clear vision of the educational demands of modern society and turned his considerable energy to the task. He founded the Christian School Association in Orloff in 1820 and, through it, developed a rigorous standard curriculum and founded teacher training institutes. In this, he was supported by Russian authorities who saw educational development as essential to economic development.xcvii

The reforms pushed by Cornies marked a transition to a meritocratic model of education, aiming to identify and develop the best minds for responsible positions, as opposed to reinforcing tradition and the inherited world view. By the time of his death (1840), the schools of Molochnai featured a standardized curriculum, with little room or interest in Schönschreiben, in a highly regulated environment, in spite of reported opposition from many in the community.xcviii

Fraktur in the Russian Schools

The earliest schools in the Russian settlements were taught by farmers and craftsmen who usually taught at their places of work. Basic literacy was the qualification.xcix Fraktur, and especially the vorschrift, has a curricular role but an aesthetic one, too. Spending time on fraktur, then, probably was driven by the strength of inherited cultural tradition shared by teacher and student and the time devoted to schooling. Those values varied by colony but was strongest among the Mennonites.

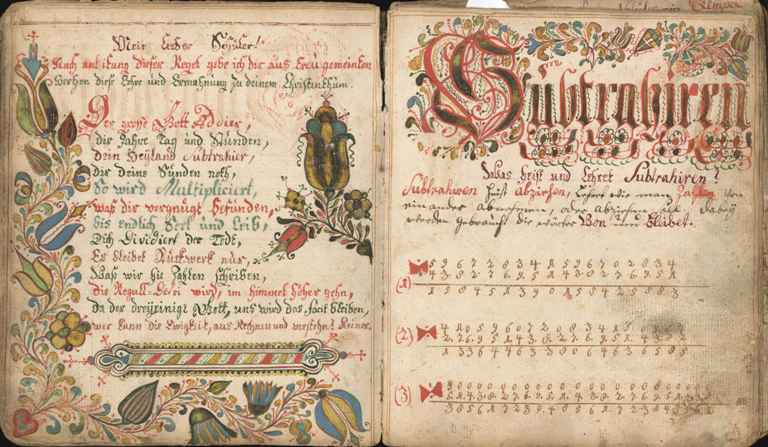

The early curriculum of Mennonite schools included not only reading, writing and arithmetic but also penmanship, often expressed as stylized calligraphy related to fraktur. “Schönschreiben” is reportedly described in handwritten school plans of several Mennonite teachers in the Molotschna colony.c Vorschriften, awards of merit (see illustration 3), decorated arithmetic books were commonly found (see illustrations 4 and 5), among other types. The first, the vorschrift, was a copy exercise, drawn originally by the schoolmaster and from which copies were executed by pupils. Awards of merit were drawn by the teacher and selectively presented to students as a motivational device. Decoration of arithmetic copy books using fraktur figures was a tradition especially common in Russia, unlike the first two, which were universal in Mennonite schools.

In December, significant time was devoted to another distinctively Russian-German practice. Pupils would write or copy a poem or essay expressing their appreciation of their parents and decorate it with fraktur motifs. On Christmas morning, the child would read or recite the text and present their work to their parents. Other gift-giving followed.ci New Year’s wishes were also common (see illustration 6).

The early days of the Cornies-led reform movement continued the Fraktur tradition. The highly educated Prussian teachers called to the colony’s new teacher training school at Orloff, Tobias Voth, followed by Heinrich Hesse, both were adept at Fraktur-Schönschreiben, which they emphasized in their teacher training.cii That drawing and decoration of some kind was important is shown by Hesse’s inclusion of straight edges, pens and water color among the essential school supplies in 1841.ciii

The presumptions of the reform movement that brought Voth and Hesse to Russia, however, ultimately proved to be the destruction of the practice of fraktur drawing in Russian-German schools. The more rigorous and time consuming modern curriculum meant that the time formerly devoted to calligraphic penmanship and decoration was no longer available. Teachers no longer had time nor inclination to continue the tradition of drawing rewards of merit. Printed copy books were available to help teach the alphabet, rather than drawing one’s own. Where the traditional hand-drawn specimens continued, their quality clearly deteriorated by mid-nineteenth century.civ

Russian-German Education in the U.S.

Russian-German cultural assumptions changed in the American environment and fraktur in the schools did not long survive the transition. In the U.S., the immigrants found a culture that assumed education to be the right of every individual and provided to all by government. These beliefs are often attributed to Thomas Jefferson’s advocacy of universal education and were expressed in the great plains settlement through the provision of one section within each township of thirty-six sections for the support of the “common school.”cv The 1871 school law of Kansas required all parents of children between eight and fourteen to send the child to a public school with a “competent instructor” for at least twelve weeks each year, six weeks of which had to be consecutive.”cvi It was clear that, in the U.S., public education would be the dominant mode.

While it has been common throughout U.S. history for new groups to establish their own parochial schools to provide religious and language instruction to children, practical realities often limit their lifespan to little more than a generation. Indeed, Mennonite immigrants initially set up elementary schools that replicated those in Russia, the first in Kansas being a sod building in Gnadenau established in 1874.cvii Many of the 18,000 Mennonite settlers of the midwestern states did the same, leading to a delicate coexistence of the parochial with the better funded public school systems.

Mennonites did not take an adversarial stance against public schools and implicitly recognized their central role in the new society. The 1877 Western District conference of Mennonite teachers and ministers advocated instead that their members attempt to influence if not dominate the local schools and found church schools only where that was not feasible. They also recommended including English in the curriculum, the better to communicate with neighbors.cviii What a change from their Russian experience!

The ensuing period of uneasy coexistence of parochial and public schools sometimes included clever stratagems by the former. Sometimes, a bilingual teacher would be hired through the public school system, compensated rather handsomely but then obligated to teach in the off-hours at the parochial school for little or no money. The German Teachers’ Association itself had to take a stance against this practice.cix More often, the parochial teachers took the county public school examination and brought their schools into the system, finding what opportunity they could to instruct in their special language and history.cx The recognition grew that success in the U.S. depended on learning what the public schools had to offer.

The modern school curriculum had little room for creating decorated manuscripts, even had the cultural need been present. The early Mennonite parochial schools included writing exercises based on copy book examples and emphasizing Schönschreiben. An early teacher’s guide recommended devoting three hours per week to the practice.cxi Rather than continuing with homemade copy books, however, the first Mennonite Teachers’ conference in Kansas (1877) discussed the need for standard textbooks “so that the whole school system elementary and central, could be made uniform.”cxii

Fraktur continued to be created in the United States to only a limited degree and quickly declined with the demise of the private schools.cxiii A few gifted students, having been exposed to the tradition, drew specimens on their own and a few practitioners produced pieces upon request. Artist Benjamin A. Ratzleff was still drawing Weinachts Wünsche and religious mottoes into the 1930’s.

Perhaps the ultimate cause of the demise of the traditional schools and fraktur, though, is, ironically, the triumph of the progressive vision of Johann Cornies. As it was put in a contemporary account (A Day with the Mennonites, 1889):

If the sons and daughters of [pioneers] Peter Schmidt of Emmatal and Heinrich Reichert of Blumenfeld will walk in the ways of those worthy men, the result will be something like a fairyland . . . and the richest farmers of Kansas will dwell therein.

But there is danger this will not come to pass. Jacob and David [their sons] will go to work on the railroad and let the plow take care of itself; and Susanna and Aganetha will go out to service in the towns, and fall to wearing fine clothes and marrying American gentiles . . .”cxiv

The irony of the passage is that it is the “gentile” commentator expressing nostalgia for the lost ways of Mennonite tradition, which he never experienced. Jacob, David, Susanna and Aganetha, if typical, would have been eager to move on.

Education in Pennsylvania

From the viewpoint of nurturing cultural tradition in the schools, the German immigrants to Pennsylvania were advantaged by perfect timing. As a standard history puts it,

“. . . the rural schools of the early nineteenth century reflected the close local control, the broad parental discipline, the parsimony and the limited educational needs of rural communities in the early American republic.” Further, “Rural district schools were much the same in 1830 as they had been in 1780.”cxv

Indeed, local communities were powerful in colonial Pennsylvania because of William Penn’s frequent absence from the colony and his own liberal attitude toward local authority. The latter gained power in the course of the eighteenth century at the expense of the proprietor and his council. Among the beneficiaries were local elected officials and religious and economic leaders.cxvi

The dominant form of school in the middle Atlantic states was the subscription school, a form of private but not parochial organization and Mennonites founded many of them, along with other groups. By 1776, there were at least sixteen subscription schools founded by Mennonites in Pennsylvania.cxvii The primary focus of these, and other schools of the time, were scripture, biblical teaching, rudimentary Latin, spelling and morals.

Reflecting the nature of rural Pennsylvania society, the subscription schools were not exclusive to any particular group. Schools founded by Mennonites welcomed children of other groups and indeed were often taught by those of other faiths.cxviii The Mennonite-founded school of Lower Salford in 1758 was governed by a board of trustees that included Dunkers, Lutherans and Reformed as well as their own representatives. The charter of the Mennonite school of Earl Township in Lancaster County specified that seven of twelve trustees be Mennonite but that the pupils could be “of whatever denomination soever.”cxix

The religious subscription schools featured similar curricula regardless of the founding denomination. Often the only books were a primer and the New Testament. Pupils copied out penmanship examples, thus providing a role for the vorschrift. Rewards of merit were distributed by the schoolmaster and hymnbooks were often decorated with ownership statements. The curriculum (and, often, vorschriften) included English as well as German.

This pattern lasted until notions of national progress, educational improvement and equitable opportunity led to passage of the free schools act of 1834. This legislation permitted local taxation and the establishment of common township schools, free from church affiliation. Many Pennsylvania Germans saw this as a threat to their culture. Of 987 potential school districts in the state, 264 initially refused the community school plan, most in Pennsylvania German counties.cxx In 1849, the remaining 200 were forced to establish public schools and the process was complete by the early 1850’s.cxxi

CONCLUSIONS

The few studies of fraktur among the Russian-Germans show that it flourished from about 1760 – 1850, about the same period in which the Pennsylvania Germans were producing so much work. Among the Russian-Germans, however, it was almost exclusively the Prussian Mennonites of the Vistula and those who subsequently settled in Molotschna to whom we are able to attribute authorship. There are also some pieces from the Chortitza colony. While the Lutherans and Reformed drew most of the pieces found in the Pennsylvania German oeuvre (in the form of taufscheine), these groups are absent from the Russian-German inventory.

This paper suggests that widespread drawing of fraktur is found among groups that have reached a particular place in their economic and cultural development, involving multiple characteristics that must work with each other to render a society likely to produce this form of traditional material culture.

Among the German-speaking emigrant groups of the late-eighteenth/early-nineteen centuries, those whose survival was seriously threatened or whose basic well-being was stressed were not among the fraktur producing groups. The pre-1740 Pennsylvania settlers and the Volga colony before the late nineteenth century, for example, were distracted in this manner. Life was not easy for the post-1740 Pennsylvania Germans, the Prussian and the Molotschna Mennonites but, relative to analogous groups, they had a reputation for prosperity and security. It is groups in the later category that tend to produce fraktur.

Fraktur is obviously an expression of German folk identity and the culture that is likely to produce it is one that perceives itself to be cohesive, independent and clear in its shared beliefs. The permissive administration of William Penn’s colony allowed the development of such distinctives without stifling control from above. The resulting self-confident security of the church-based groups encouraged their cooperation and development of an over-arching identity as Pennsylvania Germans. The Mennonites of Prussia and Russia maintained this degree of cultural cohesiveness. The Lutherans and Reformed, without the heritage and negotiating power of such strong local communities, were more susceptible to interference by Russian authority and the cultural balkanization of the closed village system.

The culture of a society is affected by material conditions and so the state of communication, transportation and commerce has a role. Fraktur production seems to be associated with a middle ground between the purely subsistence economy and that of capital-intense dominance by commerce. Two factors may be at play. The sharing of ideas and examples within the group is facilitated by communication and transportation that reaches out at least to the region but is not so developed as to overwhelm the local with products and ideas from the national level. This roughly describes Pennsylvania in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when fraktur flourished. Conditions in Russia hampered such communication until the late nineteenth century, well into the period when national industrial and commercial advancement was the ideal.

The second factor relating to material and economic development is the idea that folk expression, such as fraktur, is a reactive response to the leading edge of commercial development. In this hypothesis, fraktur flourishes at an early stage of a economic and cultural progression that inevitably leads to its being left behind. This possibility depends, in turn, on the presence of a strong folk identity in the first place. Given that, it may well be that elements of the culture are more celebrated when perceived to be under threat than would otherwise be the case. The Russian-German Mennonite community fulfilled this criterion.

The idea of the middle ground in a development path that leads inevitably to modern systems applies to education, as well. Since much fraktur, especially among Mennonites, is part of pedagogy, a strong elementary school system is a prerequisite. We find this among the Pennsylvania Germans and the Molotschna Mennonites, the other settlements being more challenged in this regard during the early nineteenth century. Fraktur seems to flourish in a strong locally-governed school system that has not reached the point of substituting a modern pedagogy and curriculum for the traditional. By the mid-nineteenth century, in all the cases we examined, the transition was well under way.

Acknowledgments

Ethel Ewert Abrahams was most generous with access to her research materials, especially her extensive collection of reproductions of Mennonite fraktur. The staff of the Mennonite Church USA Archives, Bethel College, Kansas, were also very helpful in this research.

NOTES

1 Ethel Ewert Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften Among the Dutch-German Mennonites, submitted to the Department of Art Education and the Faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Wichita: Wichita State University, 1975), 6.

2 Ethel Ewert Abrahams, Frakturmalen und Schönschreiben, The Fraktur Art and Penmanship of the Dutch-German Mennonites While in Europe (North Newton, KS: Mennonite Press, 1980), 8.

3 Lavern J. Rippley, “Black Sea and Volga Germans in 1763, 1804, and 1910,” Heritage Review 24 (September 1979): 4.

4 Adam Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, the Story of Russia’s Germans (Winnipeg: the author, 1974), 5.

5 Arnold H. Marzolf, “Pietism and the German-Russians,” Heritage Review 22 (September, 1992): 5.

6 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 19.

7 Ibid., 19.

8 Horst Gerlach, “From West Prussia to Russia, 1789-1989, Background and Significance of the Mennonite Emigration,” Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 17, no. 2 (Summer, 1994): 11-13.

9 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften , 10.

10 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 31.

11 Michael Miller, Researching the Germans from Russia, Annotated Bibliography of Germans from Russia Heritage Collection at North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies (Fargo: the Institute, 1987), xvii.

12 Rippley, “Black Sea and Volga Germans,“ 24:4.

13 Walter Kuhn, “Cultural Achievements of the Chortitza Mennonites,” Mennonite Life III, no. 3 (July, 1948): 35.

14 Rippley, “Black Sea and Volga Germans,“ 24:5.

15 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 36.

16 Ibid., 43.

17 Ibid., 76.

18 Gerlach, “From West Prussia to Russia,” 17:19, 20.

19 Norman Saul, “The Arrival of the Germans from Russia, a Centennial Perspective,” Work Paper 21, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (Fall, 1976): 97.

20 Lawrence Klippenstine, “Broken Promises or National Progress, Mennonites and the Russian State in the 1870’s,”

Journal of Mennonite Studies 18 (2000): 97.

21 Miller, Researching the Germans from Russia, xvii.

22 Klippenstine, “Broken Promises” 18:97.

23 Saul, “The Arrival of the Germans,” 21:5.

24 Ibid., 6.

25 Cornelius Krahn, “From the Steppes to the Prairies,” in Cornelius Krahn, From the Steppes to the Prairies (Newton, KS: Mennonite Publication Office, 1949), 8.

26 Edward Krehbiel, “Christian Krehbiel and the Coming of the Mennonites to Kansas,” in Cornelius Krahn, From the Steppes to the Prairies (Newton, KS: Mennonite Publication Office, 1949), 32.

27 Saul, “The Arrival of the Germans,” 21:7.

28 Edward Krehbiel, “Christian Krehbiel,” 31.

29 Noble L. Prentis, “A Day with the Mennonites,” reprinted from Kansas Miscellanies (Topeka: Kansas Publishing House: 1889) in Cornelius Krahn, From the Steppes to the Prairies (Newton, KS: Mennonite Publication Office, 1949), 20.

30 Noble L. Prentis, “The Mennonites at Home,” reprinted from Kansas Miscellanies (Topeka: Kansas Publishing House: 1889) in Cornelius Krahn, From the Steppes to the Prairies (Newton, KS: Mennonite Publication Office, 1949), 15.

31 Andrew Gulliford, America’s Country Schools (Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, 1984), 92.

32 Aaron Spencer Fogelman, Hopeful Journeys, German Immigration Settlement and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), 6.

33 Steven M. Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land, Pennsylvania Germans in the Early Republic (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2002), 14.

34 James T. Lemon, The Best Poor Man’s Country, a Geographical Study of Early Southeastern Pennsylvania (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1972), 5.

35 Fogelman, Hopeful Journeys, 97.

36 Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land, 13.

37 Lemon, The Best Poor Man’s Country, 18.

38 Ibid., 31.

39 Richard K. MacMaster, Land, Piety and Peoplehood, the Establishment of Mennonite Communities in America, 1683-1790 (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985), 126, 127.

40 Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land, 131.

41 Kempes Schnell, “John F. Funk and the Mennonite Migrations of 1873-1885,” in Cornelius Krahn, From the Steppes to the Prairies (Newton, KS: Mennonite Publication Office, 1949), 77.

42 Marzolf, “Pietism and the German-Russians,” 22:5.

43 Harm Schlomer, “Inland Empire, Russian Germans,” Heritage Review 32, no. 1 (March, 2002): 3.

44 Fred C. Koch, The Volga Germans in Russia and the Americas from 1763 to the Present (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, 1977), 43.

45 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 16.

46 Ibid.,19.

47 Marzolf, “Pietism and the German-Russians,” 22:5.

48 Koch, The Volga Germans, 42.

49 Krahn, “From the Steppes to the Prairies,” 1.

50 Conrad Keller, The German Colonies in South Russia 1804-1904, volume 1 (Lincoln, NB: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1968), 18.

51 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 32.

52 John R. Staples, “Johann Cornies, Money-lending and Modernization in Molotchna Mennonite Settlement from the 1820’s to the 1840’s,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 27 (2009): 114.

53 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 63.

54 Keller, The German Colonies, 94.

55 James Urry, None But Saints, the Transformation of Mennonite Life in Russia, 1789-1889 (Winnipeg: Hyperion Press, 1989), 21.

56 Staples, “Johann Cornies,” 27:120.

57 MacMaster, Land, Piety and Peoplehood, 110.

58 Lemon, The Best Poor Man’s Country, 27.

59 Ibid., 15.

60 Keller, The German Colonies, 88.

61 Fogelman, Hopeful Journeys, 149.

62 Robert W. Regier, The Anabaptists and Art, the Dutch Golden Age of Painting,” Mennonite Life 23, no. 1 (January, 1968): 18.

63 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften, 40.

64 Abrahams, Frakturmalen und Schönschreiben, 11.

65 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 183.

66 Marzolf, “Pietism and the German-Russians,” 22:6.

67 Adolf Ens, “Mennonite Education in Russia,” in John Friesen, editor, Mennonites in Russia, 1788-1988, Essays in Honour of Gerhard Lohrenz (Winnipeg: CMBC Publications, 1989), 75.

68 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 165.

69 Rippley, “Black Sea and Volga Germans,“ 24:5.

70 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 155.

71 Koch, The Volga Germans, 125, 126.

72 Ibid., 22:6.

73 Marzolf, “Pietism and the German-Russians,” 22:5-11.

74 Timothy Kloberdanz, The Volga Germans in Old Russia and in Western North America, Their Changing World View (Lincoln, NB: American Historical Association for Germans from Russia, 1979), 212.

75 Elena V. Ananyan, “The Problem of Preservation of National Identity of Ethnic Germans in the Volga Region and in North America and South America,” Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 33, no. 3 (Fall, 2010): 23.

76 Kuhn, “Cultural Achievements of the Chortitza Mennonites,” 3:38.

77 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften, 32.

78 Urry, None But Saints, 167.

79 Fogelman, Hopeful Journeys, 74.

80 MacMaster, Land, Piety and Peoplehood, 286.

81 Ibid., 139.

82 Lemon, The Best Poor Man’s Country, 8.

83 MacMaster, Land, Piety and Peoplehood, 185.

84 Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land, 68.

85 MacMaster, Land, Piety and Peoplehood, 170.

86 Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land, 14.

87 Urry, None But Saints, 153.

88 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften, 121.

89 Urry, None But Saints,155.

90 Melvin Gingerich, “Elementary Education,” in Mennonite Encyclopedia, volume II (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1955), 181.

91 Ethel Ewert Abrahams, “Fraktur,” Mennonite Encyclopedia, volume V (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1990): 309.

92 Urry, None But Saints,156.

93 Gingerich, “Elementary Education,”181.

94 Peter Braun, “The Educational System of the Mennonite Colonies in South Russia,” Mennonite Quarterly Review III, no. 3 (July, 1929): 169.

95 Geisinger, From Catherine to Kruschchev, 170.

96 Koch, The Volga Germans, 139.

97 Urry, None But Saints,162

98 Ibid.,163.

99 Braun, “The Educational System of the Mennonite Colonies,” III:170.

100 Ethel Ewert Abrahams, “Fraktur by Germans from Russia,” Work Paper No. 21, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (Fall. 1976): 16.

101 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften, 126.

102 Abrahams, Frakturmalen, 12.

103 Abrahams, “Fraktur by Germans from Russia,” 21:16.

104 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften, 128.

105 Gulliford, America’s Country Schools, 38.

106 H. P. Peters, History and Development of Education Among the Mennonites in Kansas, a thesis submitted to the faculty of the College of Liberal Arts in candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts (Bluffton, OH: Bluffton College, 1925), 12.

107 Gingerich, “Elementary Education,” 182.

108 Gulliford, America’s Country Schools, 93.

109 John Ellsworth Hartzler, Education Among the Mennonites of America (Danvers, IL: Central Mennonite Publications Board, 1925), 111.

110 H. P. Peters, History and Development of Education, 23.

111 Abrahams, The Art of Fraktur-Schriften, 131.

112 H. P. Peters, History and Development of Education, p.20.

113 Abrahams, “Fraktur by Germans from Russia,” 21:16.

114 Noble L. Prentis, “A Day with the Mennonites,” 24.

115 Gulliford, America’s Country Schools, 39.

116 Lemon, The Best Poor Man’s Country, 26.

117 Gingerich, “Elementary Education,” 182.

118 Mary Jane Lederach Hershey, This Teaching I Present, Fraktur from the Skippack and Salford Mennonite Meetinghouse Schools, 1747-1836 (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2003), 23.

119 MacMaster, Land, Piety and Peoplehood, 157.

120 Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land, 44.

121 Hartzler, Education Among the Mennonites, 12.7

1,777 thoughts on “FRAKTUR AND THE RUSSIAN-GERMANS”

Comments are closed.