What did fraktur mean to the people who made it and saved it? To again quote folk life scholar Don Yoder, “the first function of fraktur art is the recording of events in an individual’s life, as he or she moves through the rites of passage from one social group into the next” (Yoder, A fraktur primer, 1989). Thus, many fraktur mark life events, such as birth, baptism, graduation from school and other occasions.

The fraktur form, however, was applied to other purposes, as well. Dr. Donald Shelley claims that fraktur had three aims – to preserve a record of birth and/or baptism, emphasize a religious truth, or to present an attractive and colorful design (Shelley, 1961, p. 39). In schools, fraktur was used to teach reading, writing, the alphabet and numbers; to teach spiritual and moral truths and Scripture verses and hymns; to teach design and the love of things beautiful, and to reward students who had excelled in their studies (personal communication from Mary Jane Hershey). House blessings, religious texts, family registers and other culturally important documents received the fraktur treatment.

Fraktur was commissioned, produced and preserved by members of a distinctive and strongly religious folk culture and its meaning gets to the essence of the culture. As Dr. Yoder puts it, “fraktur is folk art, the expression of a community’s ideals and hopes in compact and visual form” (Yoder, European background, 2001, p. 57, 58).

Since they are a strongly religious people, many fraktur texts express the Pennsylvania German religious viewpoint, which is Protestant, Bible-centered and strongly influenced by the Pietistic movement. As Yoder explains, the word-centeredness and assumption of personal devotional use of fraktur is typical of the Protestant sensibility and contrasts with Catholic graphic imagery meant for display (Yoder, European background, p. 2001, p. 57, 58).

Fraktur, as Protestantism itself, is hardly uniform, however, and differences can be readily identified between the fraktur work of the “church people” (Lutheran and Reformed) and that of the Anabaptist sects (Mennonites and Schwenkfelders).

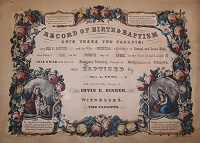

Fraktur filled a practical function, too. In the new world, civic government and established churches did not fulfill the record-producing and preservation functions in the same manner as in Europe. Individuals produced, commissioned or purchased records of, for example, birth and baptism, called Taufscheine, and often embellished in folk art style by the calligrapher or printer.

In the case of Mennonites and allied sects, the subscription schools were another important context for fraktur. The building at Deep Run, Bucks County (left, built 1842), is on the site of an historic school that was home to a series of important artists. The innovative eighteenth century educator, Christopher Dock, who taught in Mennonites schools and may have been a member of the sect himself, is credited with the idea of presenting worthy students with hand-drawn fraktur pieces as rewards. Dock also probably produced some of the earliest fraktur-style writing models for his students, called Vorschriften. This tradition was carried on by Pennsylvania German school teachers while the Taufscheine were typically drawn by a talented member of the community who may or may not have taught school (Lloyd, 2001, p. 5).

Finally, fraktur can be thought of as part of the flourishing of American folk art from about 1740 through about 1850. This may be interpreted as a sociological and historical phenomenon, as well as a religious or folk cultural one. Scott Swank sees a traditional culture dealing with the transition from a subsistence-agricultural society to a modern, market-based one. Growing prosperity may have provided the leisure and inclination to appreciate what we now know as folk art and the covert message may have been “a proudly born badge of cultural identity,” even as that identity was threatened (Swank, 1983, p. viii).

Swank’s idea of creeping modernity probably did play a role in the demise of fraktur. Printed certificates, such as this example by Currier, gradually replaced the hand drawn ones, local calligraphers were supplanted by traveling professional scriveners and taste was increasingly influenced by the national forum of ideas rather than the local. Signifiers of the traditional Pennsylvania Dutch culture became unfashionable. For example, Dutch surnames often were anglicized in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Pennsylvania legislature passed a Public School Law in 1834 that encouraged communities to create school districts, which eventually replaced the rural subscription schools. As Mary Jane Hershey points out (Hershey, 2003), the transition to English-language instruction was associated with the disappearance of this traditionally German folk art form.

2,967 thoughts on “What Does Fraktur Mean?”

Comments are closed.